Claude Monet… by Carla Rachman

Monet … grew up in an unsettled nation, rocked by political change and undergoing speedy economic development. By his teenage years in the 1850s the process of industrialization was proceeding rapidly. While encouraging wide-ranging modernization, however, the imperial establishment kept a firm grip on political power: the press was censored, the parliament tightly controlled and the unruly capital virtually taken apart as a monument to Emperor. Paris was the centre of political power, but the economic strength of the country was to be found in the east and the north.

In this picture the old city of cramped lanes and sharp divisions between rich and poor has been replaced by public spaces where everyone seems middle-class.

Monet commented on the contrast between his manner of painting the city and that practiced by contemporary English artists: ‘How could the English artists of the nineteenth century have painted houses brick by brick? They painted bricks they couldn’t see; they couldn’t possibly have seen them!’

The importance of the dealer as middleman was typical of the ‘get rich quick’ atmosphere of postwar Paris.

The First Exhibition of the Society of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers had been timed to open two weeks before the Salon to ensure plenty of press coverage.

Renoir’s brother Edmond was editing the catalogue, and when he drew Monet’s attention to the monotony of his titles – View of a Village, with variations – Monet is said to have replied, ‘Why don’t you just call them “impression”?’

There was also something in the notion of a ‘seized instant’ that intrigued the public of the 1870s, a period in which rapid change and instability were felt to be omnipresent.

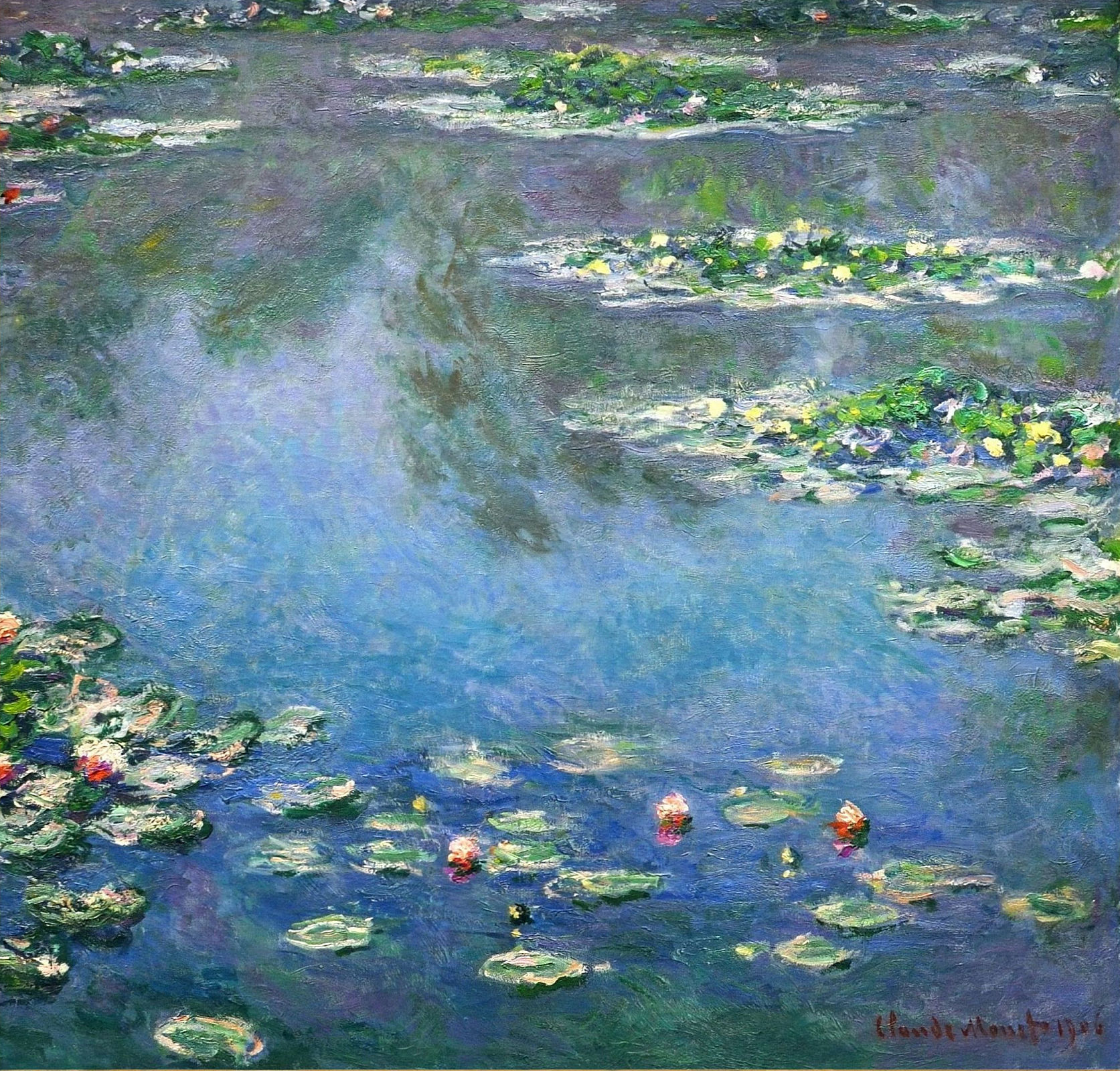

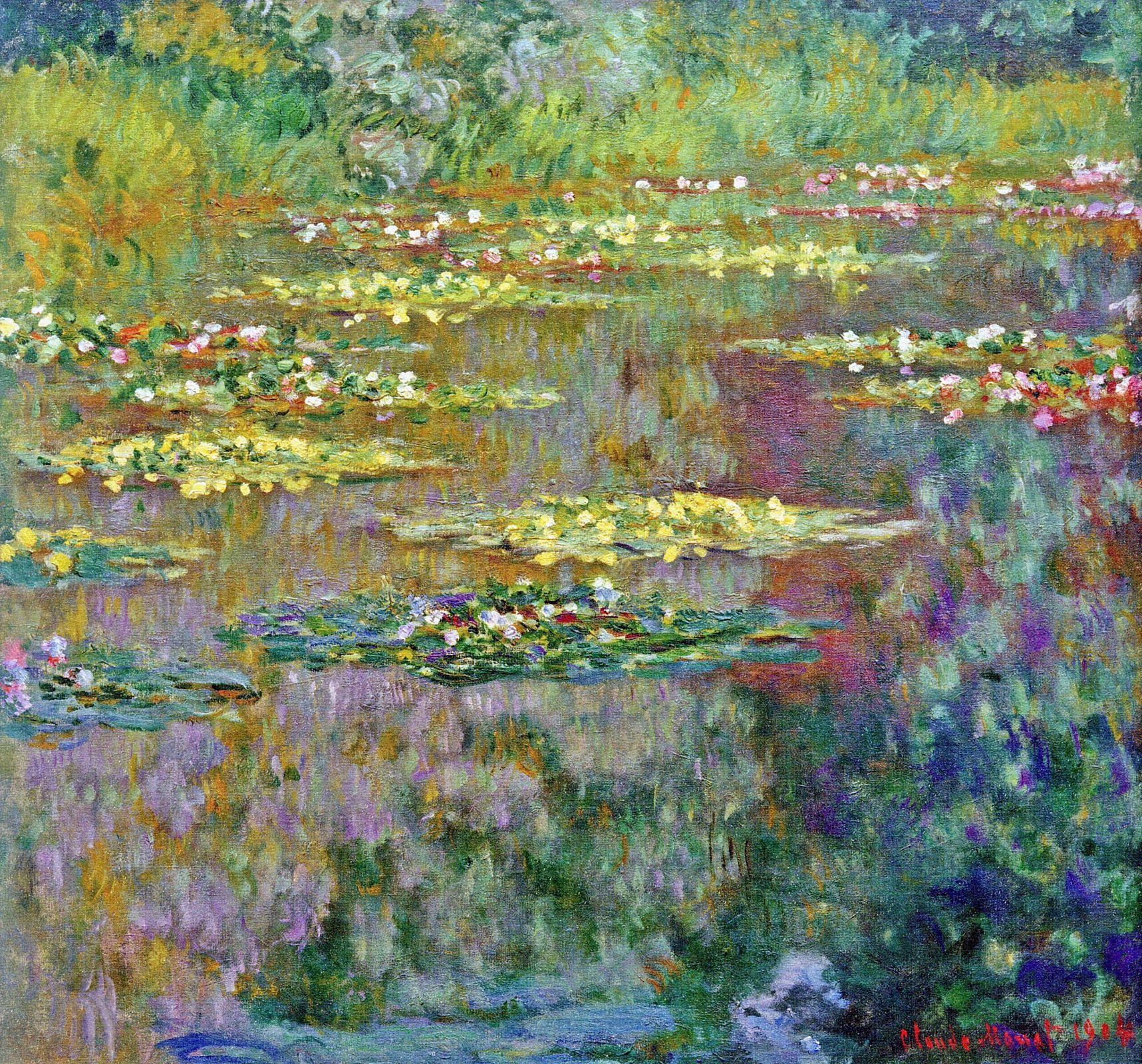

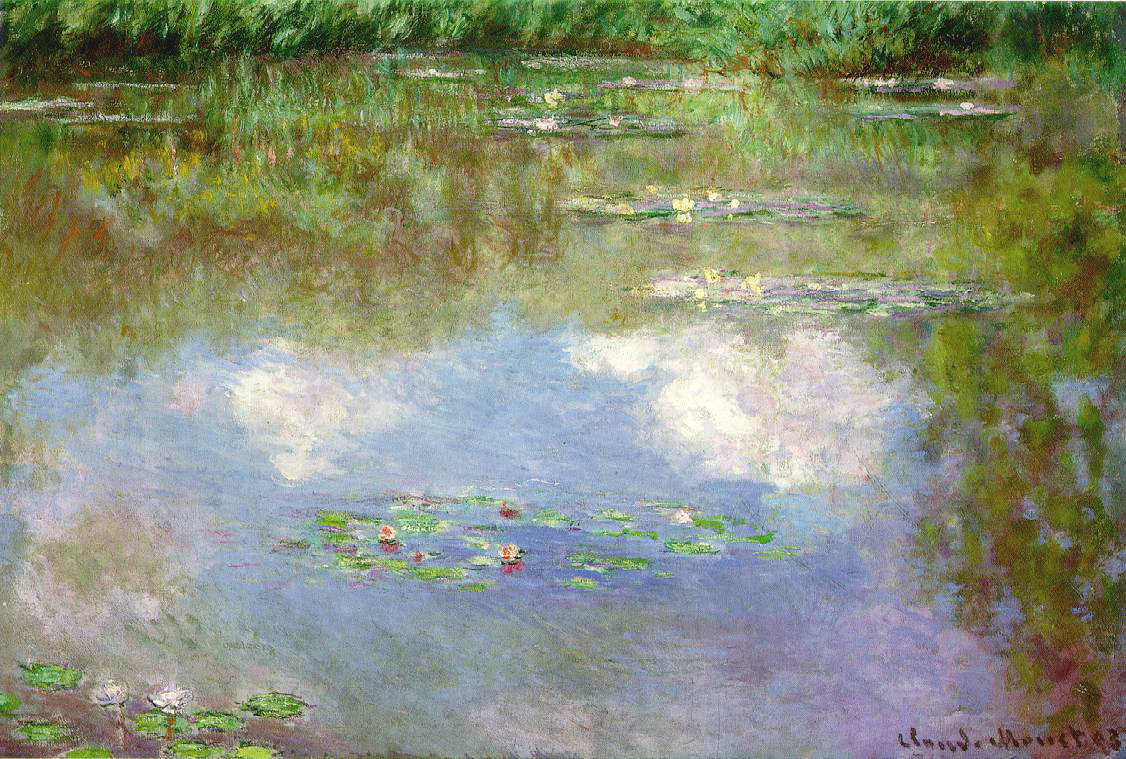

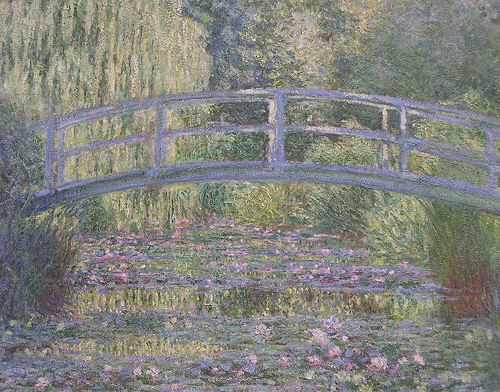

The Water-lilies series to which Monet devoted the last decades of his life was effectively a scheme of public paintings intended as a monumental legacy to France.

Although Monet was a prolific correspondent and over 2,600 of his letters survived, his statements about his work were always calculated for an audience, whether he was attempting to win or borrow money.

Monet emerges from the documentary evidence as a man with a shrewd notion of the value of his work and the importance of good public relations in achieving recognition.

Monet emerges from the documentary evidence as a man with a shrewd notion of the value of his work and the importance of good public relations in achieving recognition.

Alice (Hoschede) was unconvinced of the merits of such an approach, and when Monet expressed an interest in working from the nude with a professional model she vetoed the idea, declaring ‘If a model comes into the house, I leave it.’

Monet was striving to give the appearance of spontaneity – a snapshot with an eight-month exposure.

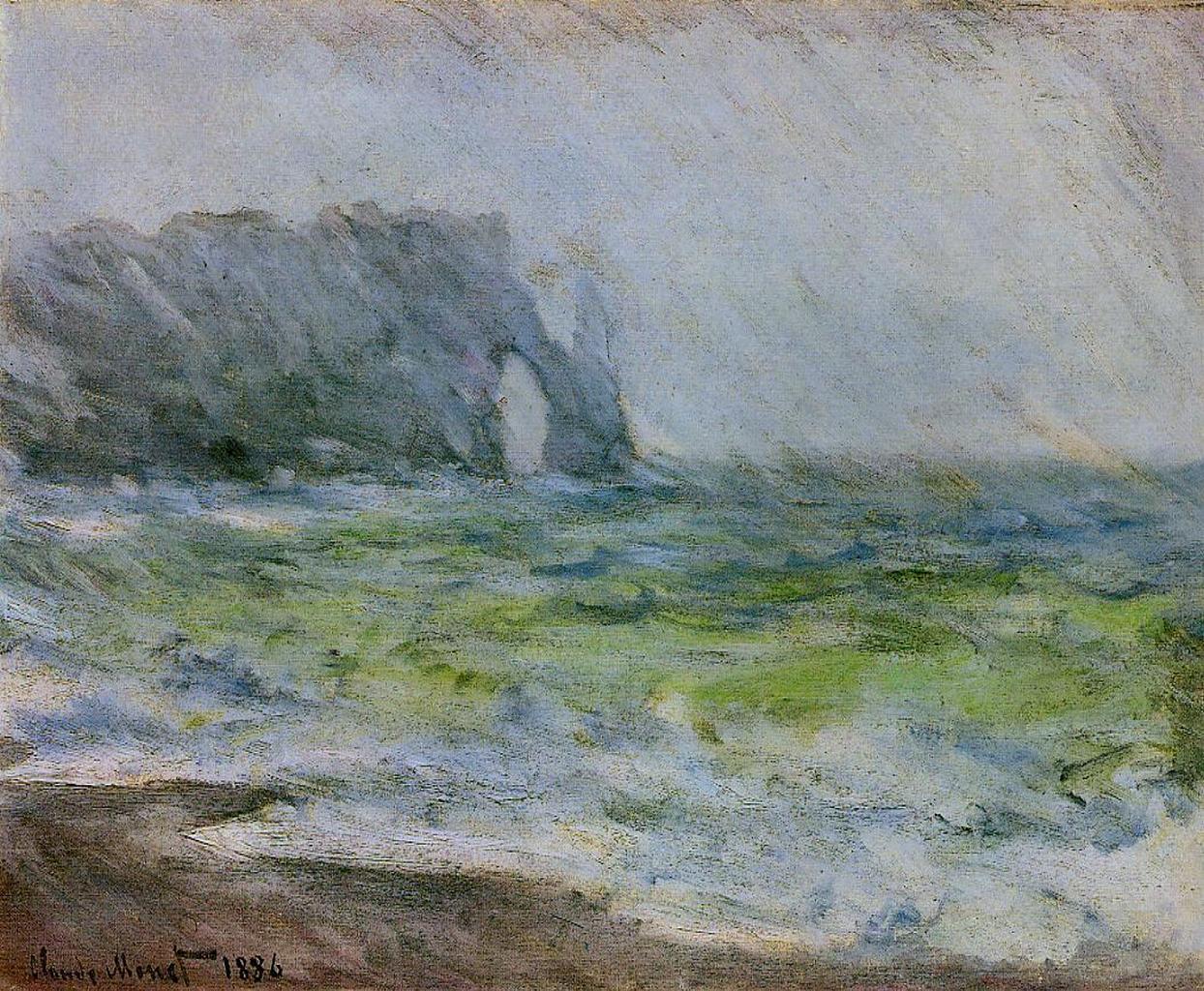

Etreat

The idea that the artist sees differently from, and better than, the rest of us is one which had always been part of the Romantic image of the artist, and by the 1880s it was beginning to replace the idea that the artist should be judged by the technical skill with which the evidence of the making of the picture is concealed.

Haute couture became a major Paris industry during the Second Empire, fuelled by the extravagances of the court and the desire of the new rich to imitate it.

The idea of an ‘impression’ as unique, the posession of a single gifted individual, was an increasingly important element in Monet’s market appeal.

p.172

The new emphasis on pictures as beatiful objects, visible in both Monet and Renoir’s work during the 1880s, needs to be seen in the context of a widespread retreat from politics and public life.

p.175

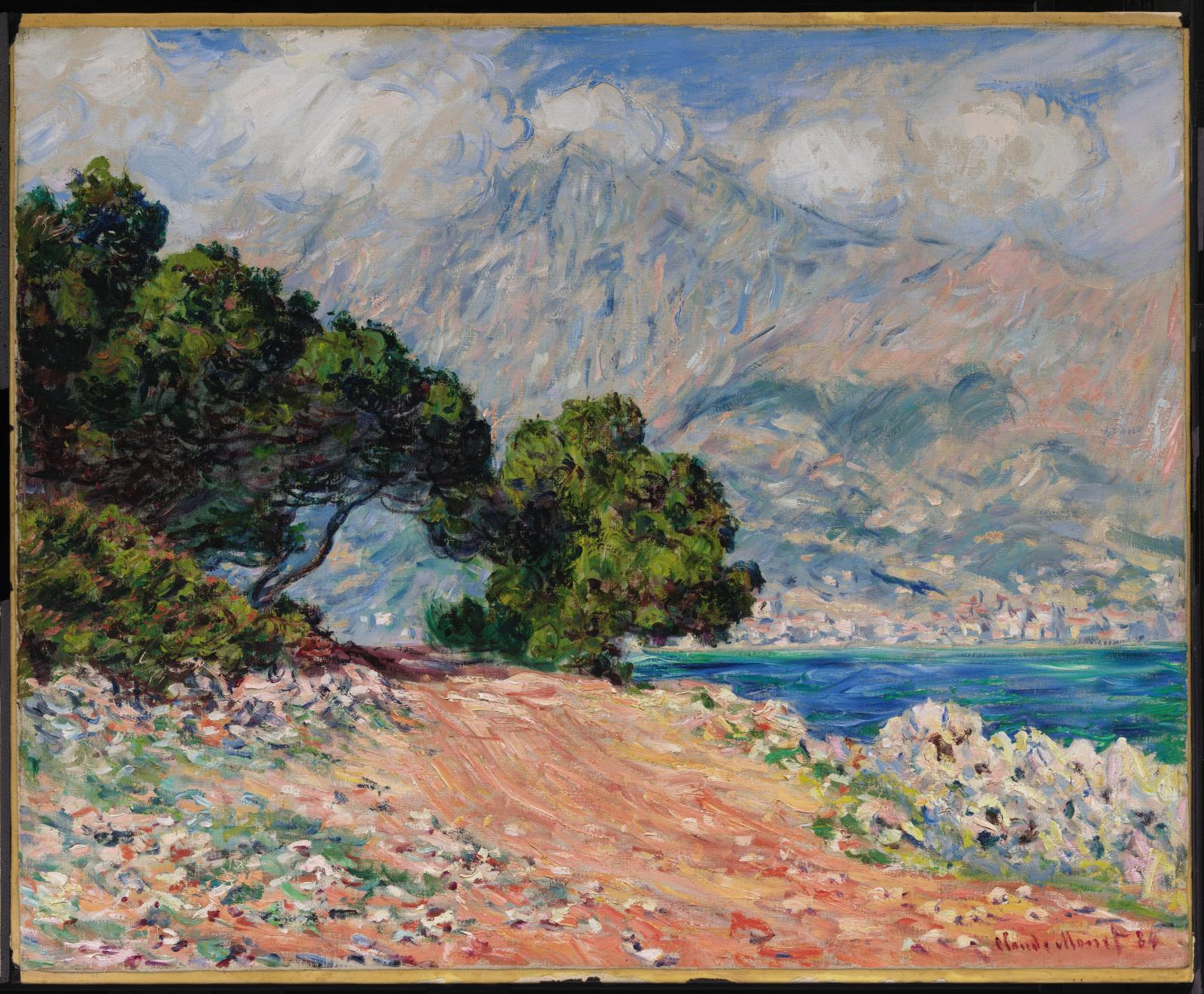

The sizzling colours, which the painter memorably described as ‘brandy-flame’ and ‘breast of pigeon’, impart a sensation of energy which is enchanced by the excited flurry of brushstrokes that cuts between orange path and ultramarine sea.

Fuelled by general prosperity and facilitated by improved road and rail links, tourism was moving to more distant areas of the country by the 1880s.

p.181

The brushwork and colouring of these mid-1880s pictures is far more abrupt nad daring that that of Monet’s earlier seascapes but it did not put off potential purchasers. By this time a certain section of the picture-buying public had actually come to value innovation more highly than tradition, and constant variation was necessary if an artist wished to stay ahead of the pack; the concept of ‘progress’ replaced ‘deviation’. Novelty had become fashionable, and the proliferation of ‘isms’ which became so marked a feature of the art world towards the end of the nineteenth century produced a situation in which a distinct style was saleable in its own right.

In the summer of 1885, when the plan was first mooted, he had complained tetchily:’I do not wish my pictures to disappear to the land of the Yankees…’

p.190

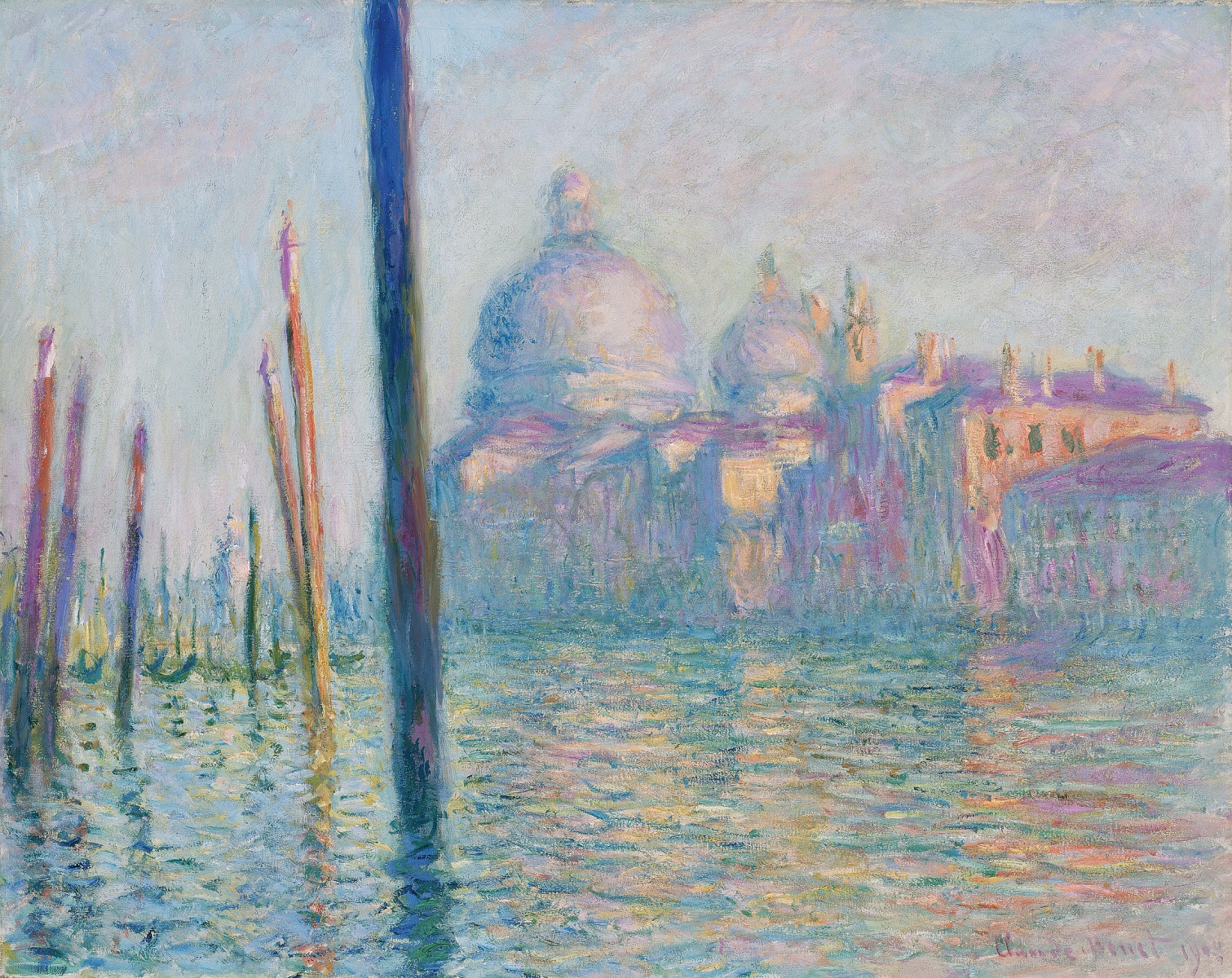

There are of course reasons why it was Monet and not, for example, Cezanne who became so desirable in the late 1880s. His pictures were less difficult, and buyers did not need to believe in the artist as they did with Cezanne. Soothing and beatiful, Monet’s landscapes were seen as truly French.

p.199

During the 1970s and 1980s the house and gardens [at Givenry] were restored at immense expense by a committee of Monet enthusiasts, mainly American.

p.211

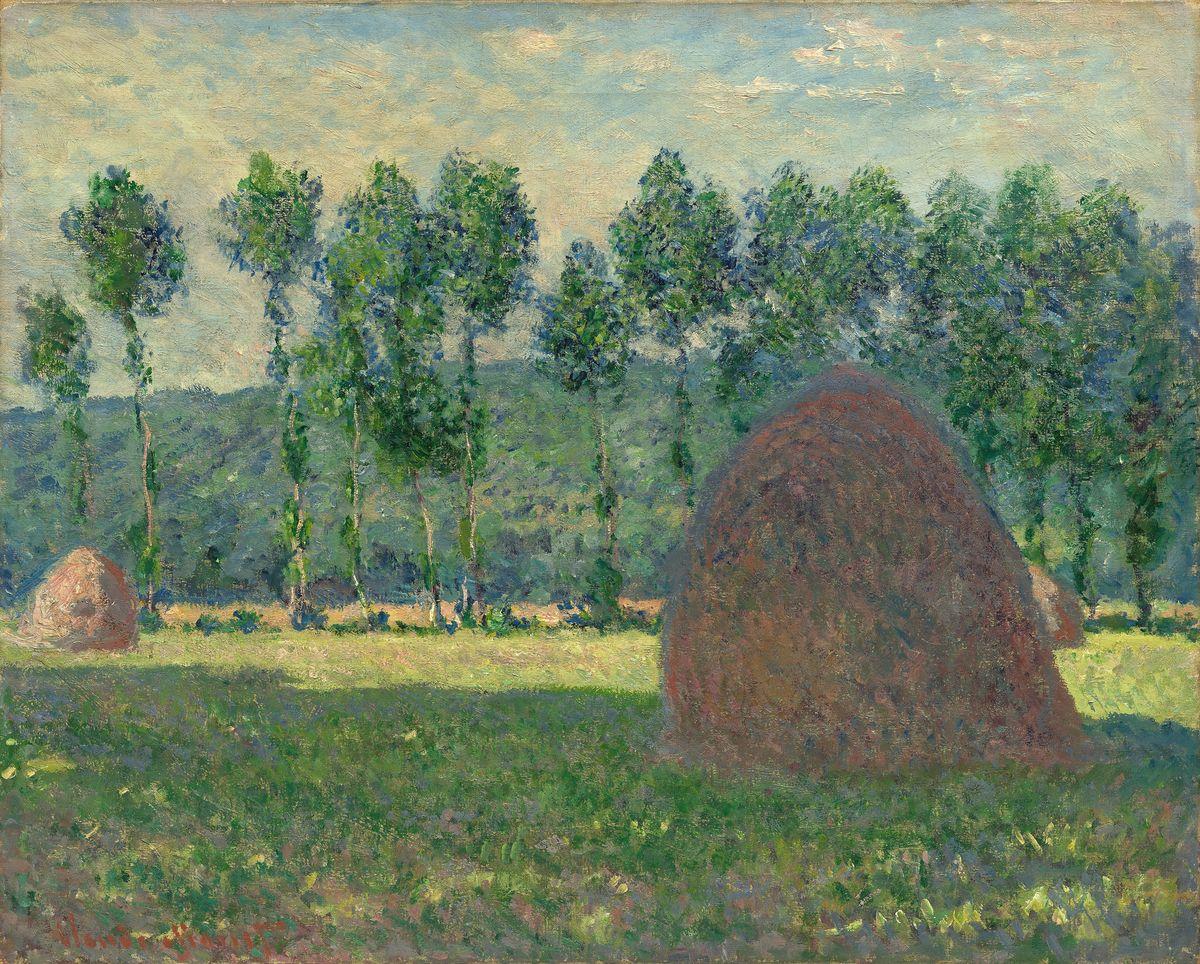

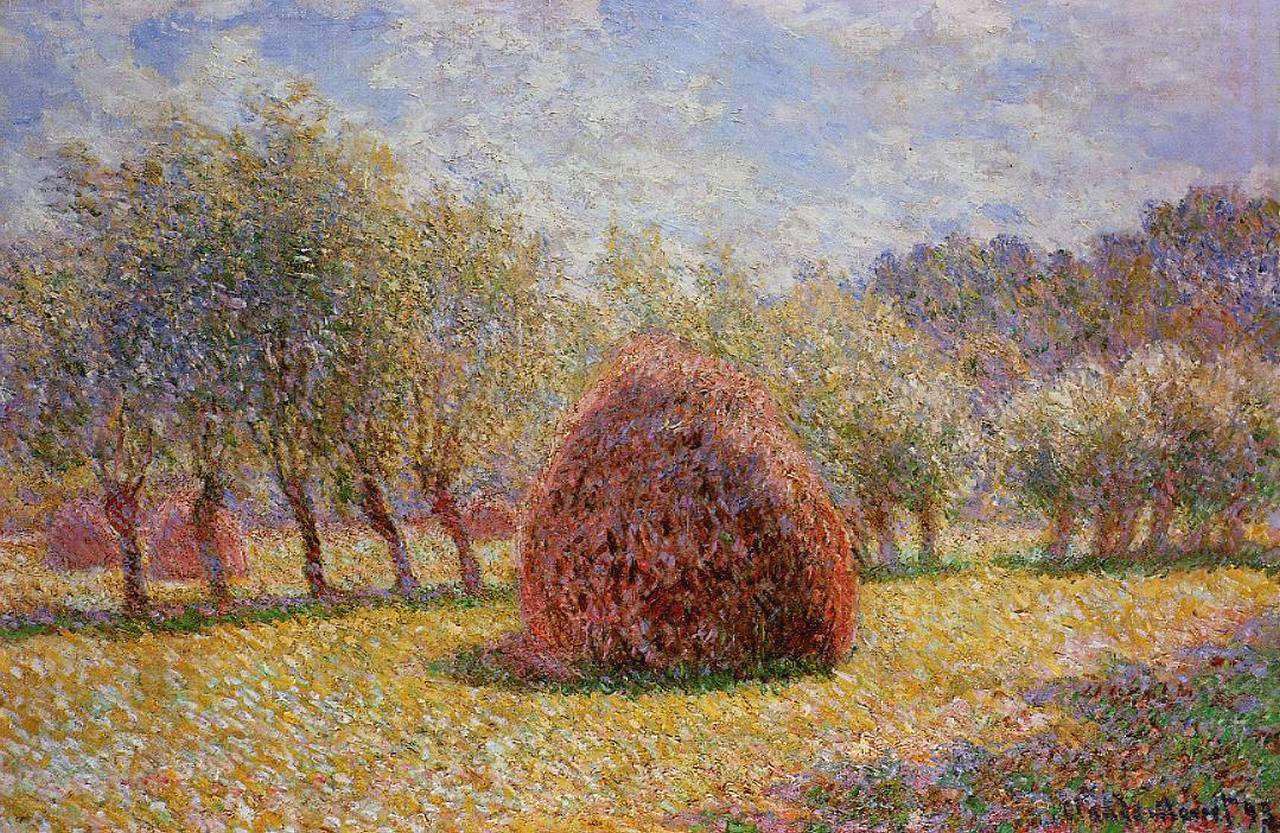

Monet himself claimed ‘To me, the motif itself is an insignificant factor; whatI want to reproduce is what lies between the motif and me.’

p.249

In the 1860s and 1870s, calling a picture decorative would have implied that it was not a serious work of art. The aim of ‘decoration’ was not to teach or inform, but to provide pleasure. However, for the avant-garde and the fashionable picture-buying public of the 1890s ‘decorative’ had weightier implications – aesthetic purity and freedom from irrelevant concerns with politics, morality or subject matter generally.

p.255

Britain and Germany had always made goods that were cheaper and perhaps sounder than those produced in France, but French products had traditionally been more stylish. By the end of the [nineteenth] century this no longer seemed to be the case. France’s rivals had set out to improve their wares through careful study.

p.258

‘I am a proud person, with a devilish self-esteem. I want to do better and I want these cathedrals to be very good’, as he wrote in immigration to an impatient Durand-Ruel.

p.260

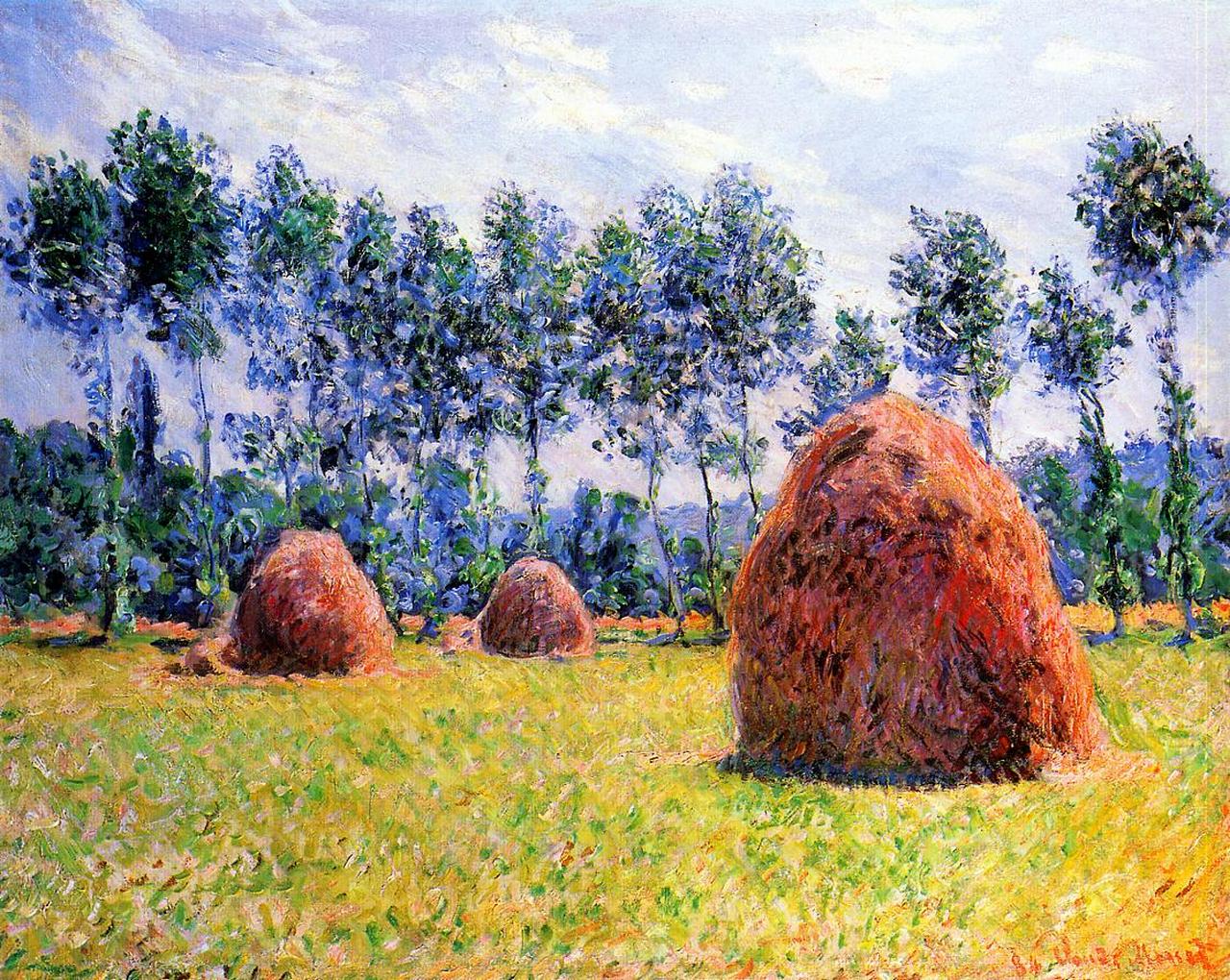

By the late 1890s his age and eminence permitted him the great luxury of painting whatever he pleased; increasingly, his works were seen not as grainstacks or cathedrals or even landscapes but simply as ‘Monets’.

p.270

The hotel’s promotional booklet actually described the foggy river views as a major advantage of the establishment, lauding ‘this soft London vapour which … melts the colours, softens the harsh protrusions and gives to buildings an air simultaneously mysterious and stylish.’ To transform polluted darkness into a tourist attraction is an impressive triumph of marketing. Monet was clearly not alone in his taste for fog.

The abolition of coal fires in the 1950s and the consequent cleaning up of London’s atmosphere has since transformed the winter air of the city, which now has seventy per cent more daylight in December than it did in Monet’s days.

p.273

The 40,000 francs spent annually on the garden was equivalent to the interest that accrued on his bank account over the same period.

p.281

‘The essense of motiff is the mirror of water whose appearance changes at every moment because areas of sky are reflected in it … The passing cloud, the freshening breeze, the seed which is poised and then falls, the wind which blows and suddenly drops, the light which dims and again brightens – all .. transform the colour and disturb the planes of water.’

p.288

The ‘oriental’ qualities of Monet’s water-lilies were often mentioned by visitors and reviewers, although in fact the flowers were African, not Asian hybrids.

p.289

For the younger generation of painters, it was Cezanne rather than Monet who pointed the way forward. Monet’s interest in colour harmonies and the surface of the picture was replaced, in Cezanne, by an obsession with the structure of the objects depicted.

p.292

By 1900 Paris has become the undisputed capital of art. It retained this position for half a century until the global balance of power shifted irretrievably at the end of World War II and New York took the lead.

In 1914 Clemenceau said to the artist, ‘Monet, you ought to hunt out a very rich Jew who would order your water-lilies as a decoration for his dining-room.’

p.297

From the original two panels the project swiftly grew to twelve and then nineteen, As the number of paintings grew, the cost soared; although the Water-lily panels were officially a gift, an extra clause was added to the Act of Donation stating that Women in the Garden would have to be bought by the state at the same time. The price-tag for this picture, at one time rejected, was 200,000 francs – an immense sum, further inflated by the fall of the franc.