Picturing Men and Women in the Dutch Golden Age… by Klaske Muizelaar and Derek Phillips

Museums were not founded in the Dutch Republic until the late nineteenth century, and not many paintings hung in churches or public buildings.

p.2

More than anything else, a woman’s honor and respectability rested on her sexual behavior: virginity was expected of the unmarried, fidelity of the married.

… Both in social stereotypes and the law, women were regarded as the more lustful sex, lying to wait to devour vulnerable males… A man trying to avoid being a slave to a woman’s unbridled passions was a common theme in jokes, songs, books, the theatre, and art works.

p.7

There was a large surplus of women throughout the seventeenth century, with four women for every three men…

Despite the strong social, religious, and legal prohibitions against intercourse prior to marriage, love between young persons, and the sexual yearnings connected with it, were widely aknowledged in Dutch society. There was a considerable toleration of sexual activity among courting couples, short of intercourse. With kweesten, or night-courting, young men spent night unsupervised in the bedrooms of their sweethearts, with the understanding that they would avid sexual intercourse, although many failed to do so.

p.13

Boys and girls from the age of six to ten attended the expensive and elite “French” secondary schools…

Both the Latin school and the universities were closed to girls..

The Dutch Republic had the highest level of literacy in Europe, measured my the ability to sign one’s name on a marriage certificate or other legal document…

Jews could become citizens, but they were excluded from guild membership as well as from much of retailing and manufacturing.

p.17

For example, Amsterdam men accused f crimes – or caught in flagrante in adultery cases – were often allowed to discharge liability of conviction through payment of a penalty…

Only men free from material want, from manual labor, and dependency on others could, they argued, devote themselves to ensuring the common good of all the city’s residents.

p.20

Rainwater or clean well-water was difficult to obtain, because it had to be fetched, often from some distance. Ordinary people usually drank milk or beer instead…

Head lice were picked out rather than washed away

p.26

Each of the new mantions contained a zaal (also spelled sael and saal), the most important and formal room in the house.

p.33

the wealthy had their laundry washed elsewhere, but brought it home to dry in the attic

p.38

Most people ate with knife, spoon, and their fingers. Only the social classes owned and used forks. In the general absense of water for washing their hands, people made wide use of napkins.

p.41

…it is safe to assume that most domestic objects were acquired on particular occasions: at marriage, the birth of children, and the death of parents.

p.42

Since relatively few rooms had a specialised function as bedrooms, most rooms were used for sleeping.

p.46

According to one scholar, the Blaeu atlas was the most expensive printed book of the second half of the seventeenth century. It was designed exlusively for “those members of the patriciate who could command both the material and the intellectual resources that were needed to buy it and to appreciate it”, and the Unitied Republic would present it as a gift to royal and other distinguished personages.

p. 50

Even if signing was common in the family circle or with frineds, playing a musical instrument must have been rare.

…

In the early seventeenth century, porcelain was known as white gold and was valuable as gold or precious jewels. All porcelain then came frm China, and later from Japan.

p. 52

In an apparent endeavor to convey an appearance of harmony, peace, and serenity, Dutch artists depicted rooms as ordered and uncluttered.

p.54

It is not known how painting were arranged in Dutch homes in the seventeenth century… and the mosst useful sources are paintings of domestic interriors and surviving dolls’ houses.

p. 61

Artists worked hard to improve the appearance of their sitters, particulary the faces. They did this mainly by eliminating various features that were considered undesirable, such as the scars or pork-marks caused by smallpox and other disfiguring deseases. Portraits rarely show moles, warts, freckles, large pores, bad complexions, facial hair among women, bags under the eyes, bulgin or squinty eyes, or unususally long or short necks. There are few flat or wide noses, big ears, receding or double chins. Even wrinkles were uncommon, No one has yellow or discolored teeth.

p.67

In the Middle Ages, the contemplation of a nude female body was regarded as sinful spying, and it was not until the eraly sixteenth century that such biblical subjects as Lot and his daughters and Susanna and the elders began to be represented with nude figures. Bthsheba, Salome, and Judith were also popular religious subjects in which female nudity (complete or ratial) was portrayed.

p.89

Fugure shos Hendrick Goltzius’s interpretation of this theme. The nipples of one of the daughter’s breasts are erect, as in many paintings in which a young woman’s bare breast are displayed.

p.90

Some appealed to a voyeuristic impulse, as in the Susanna story, where a woman is spied upon while bathing. The fact that she is being watched makes a beatiful woman even more enticing.

p.91

Rubens shows a beautiful young woman giving her breast to her father to suck, and the viewer’s attention is drawn to a part of the body associated with sex and sensuality. As Freedberg notes, the image “blatantly, almost palpably, arouses the senses. Furthermore, it does so sexually, or at the very minimum could do so.”

p.104

At the same time, they (women) were regarded as lustful and in need of protection against their won sexuality. A woman’s lasciviousness was a matter of physiological predetermination, and was evidence of her inferiority.

p.111

In his Metamorphoses, the myth of the wise Tiresias, who experienced sex both as a man and as a woman, makes it clear that women get more pleasure out of sex than men do. Tiresias had come upon two snakes coupling, had struck them with his staff, and was miraculously changed into a woman for seven years. When called upon to settle argument between Jupiter and Juno about whether men or women felt more pleasure in sexual intercourse, Tiresias replied that women ded.

p.112

For example, there are few depictions of men and women in foreign – or regional – costumes, despite the high proportion of immigrants in Amsterdam and elsewhere in the Dutch Republic.

…

Sutton notes the surprisingly few genre paintings showing sailors, dock workers, or merchant marines, a group that may have made up as much as one-tenth of the Dutch population.

p.114

Some modern scholars have claimed that such paintings, like high-life genres, had a didactic function and were viewed as warnings against the dangers of various earthy enjoyments. According to one, the “joyful, often coarse domestic and tavern scenes have been convincingly established as instructive lessons, warnings against sin, recalling death, challenging the viewer to lead a God-fearing life.”

p.127

The paintings must have had other functions. For one, depictions of peasants and their simple pleasures and surroundings must have provided humor and entertainment.

p.128

Women’s leg had a sort of mesmerizing power if accidentally exposed, and here the painter allows the male viewer a peek at what was ordinarily forbidden. The theme was a low-life counterpart to the paintings of women attending to their toilet depicted by Titian and other Italian artists, variation of which hung in some Amsterdam homes.

p.131

In Renaissance Italy, Alberti had written that portrayals of beautiful nude boys and handsome and diginfied men were appropriate for the conjugal chamber. It was thought that these paintings could influence sex and appearance of future offspring through a sort of visual imprinting.

p.143

Manuth claims that a display of cleavage was rare in the Dutch Republic, except at the “internationally-oriented court” in the Hague, and that such an attire would immediately identify a woman as a prostitute.

…

Some wealtyh Dutch women chose – or were perhaps persuaded by their husbands – to be protrayed as a shepherdess or other mythological figure. Like a “Portrait of Amelia van Anhalt Dessab and Her Son”, painted by Gerard de Lairesse in 1683. Their pose, and her bare breast, indicate that the painting is intended to depict Venus and Cupid.

p.149

The Dutch had a generally open attitude toward sexuality and eroticism in the theatre, popular books, poetry, and paintings. Most jokes, either directly or indirectly, concerned sex.

p.151

Foreign visitors often remarked on the enormous freedom that young people enjoyed in the Dutch Republic, and it does appear that courting was more often outside parental control than was the case elsewhere in Europe.

..

While unmarrried men could be forgiven for visiting brothels in search of sexual satisfaction, nothing similar was available for women.

p.154

Jews were a notable exception, for they were legally forbidden from marrying or having sexual relations with Christians.

…

University students also enjoyed rich men’s justice in matters of sexual misconduct. This was clear at the University of Leiden, where students were notoriously badly behaved.

p.156

There was, as Mijnhardt notes, “hardly any cataloguing of sexual variations, nor any substantial discussion of mastrubation, sodomy, incest, or homosexuality. Many sexual and erotic guidebooks also appeared, one even depicting an Amsterdam “dildo-shop” on its title page. The most popular was the Dutch adaptation of Nicolas Venette’s well-known manual Tableau de l’amour, published in Dutch as Venus minisieke gasthuis (Venus’ guesthouse for lovers), in which diverse variations of sexual intercourse and different ways of obtaining maximum sexual pleasure were frankly discussed.

p.158

Lacking a firm basis for self-esteem, it would not be surprising if many women were preoccupied with their physical appearance.

…

Like many visual images today, then, the pictures in wealthy Amsterdam homes must have reflected and helped shape women’s self-images, attitudes, and behavior.

p.168

The disposition of a family estate was always specified by husband and wife in their marital agreement, although these were often amended in the following years. A detailed inventory of all goods and possessions had to be prepared within a year of the deceased party’s death.

p.171

Instead, the fortune and afame of individual artists benefited from the presence of their paintings in wealthy Dutch homes.

…

“by 1800 more than 90 percent of the paintings existing around 1700 had been lost.”

…

In accounting for this low survival rate, van der Woude points to some of the conditions destructive of paintings in pre-modern Europe: the extreme dampness of most houses, the open fires that created smoke, soot, and vapor, which became attached to everything, and the harmful effects of candles and oil used for lighting.

p.173

In our exploration of the role of paintings in the domestic and imaginative lives of people three centuries ago we reject this commitment to art for art’s sake. Our concern throughout has been with art for life’s sake among men and women in the Dutch Golden Age.

p.174

Appraising the monetary worth of paintings and other material goods was a saparate task from describing them. … Licensed by the city of Amstredam, this function was always fulfilled by a woman called schatster.

p.177

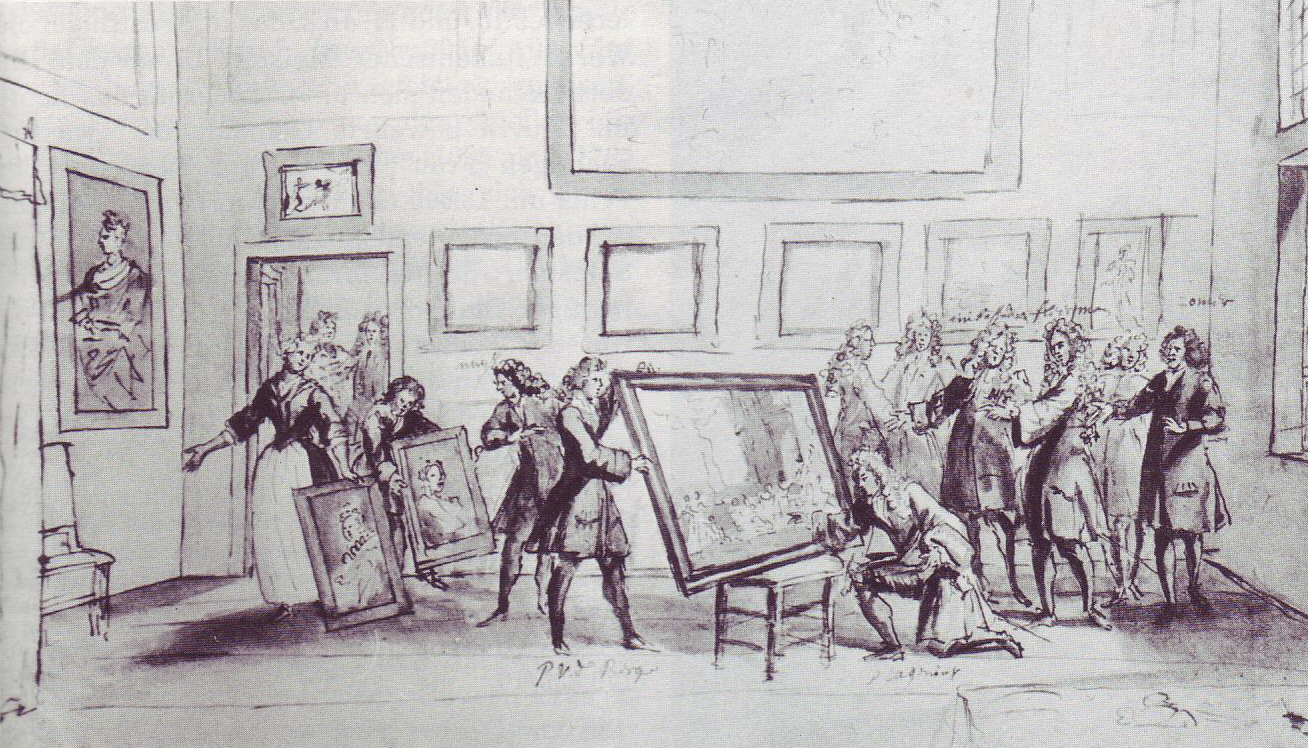

Towards the end of the seventeenth century, the art market in certain European countries began to be dictated by public auctions: first in Amsterdam, then in London and Paris.

Book info:

http://www.yalebooks.co.uk/yale/display.asp?K=9780300098174&sf1=author&st1=Klaske%20Muizelaar&m=1&dc=1

http://search.barnesandnoble.com/booksearch/isbninquiry.asp?ean=9780300098174&

http://www.amazon.com/Picturing-Men-Women-Dutch-Golden/dp/0300098170

http://www.caareviews.org/reviews/608