Fashion Brands – Branding Style from Armani to Zara

p.14

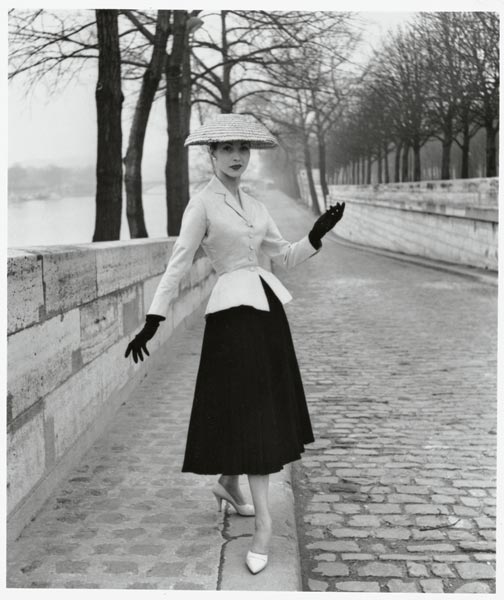

The 1950s saw the rise of Christian Dior… More than anybody before him, Dior realized that luxury could be repackaged as a mass product. Not only that, he considered it is the key to the survival and profitability of a brand.

p.16

Throughout the 1970s, the democratization of fashion continued apace. Art schools pumped out rebellious young designers, rock fell in love with avant-garde clothing, the fashion press exploded and the first generation of “stylists” – those benign dictators of dress – told consumers what to wear and how to wear it.

p.16

As early as 1965, the Italian leather goods and fur business Fendi was working with a talented young designer called Karl Lagerfeld, who helped to turn the small company into ravishing brand.

p.17

When did fashion stop being fashionable? …Probably the rot set in around the mid- to late 19080s… More than anything, though, this was the era of the yuppie, the young upwardly mobile professional, whose clothing signified success. Giorgio Armani’s unstructured but easily identifiable suits were worn as a badge of success.

p.18

She[Teri Agins] goes on to say that Lauren’s stores “stirred all kinds of longings in people, the dream that the upwardly mobile shared for prestige, wealth and exotic adventure.”

…

Ralph Lauren was the perfect brand for the 1980s, when fashion became less important that “lifestyle”. In fact, with the rise of the supermodel, the media seemed more interested in how the models lived than in the clothes they wore.

p.19

In addition, the Paris catwalks had lost their relevance in the face of MTV culture and street wear. Levi’s, Nike and Gap seemed a lot more connected to quotidian reality than some ethereal vision on a runway.

p.20

…previously everything that bore the Gucci name had been brown, soft, and rounded. With him [Tom Ford], it became balck, hard, and square.”

So what did the Gucci name mean, exactly? It meant sex. Ford brought lust back into fashion with a series of overtly erotic ads that were quickly tagged “porno chick”.

… (Ford) created clothes people wanted to wear, and then he explained to them that if they couldn’t afford the dress, they could at least by the sunglasses.”

p.21

At the same time, Miuccia Prada – with the aid of her husband and business partner Partizio Bertelli – was blowing off the dust of the old family luggage firm in Milan. …Taking the opposite stance to Gucci’s sex-drengched imagery, Miuccia positioned her brand as creative, sensitive and politically engaged. …The Prada bag replaced the Filofax as the status symbol of choice, and the shoes and clothing quickly followed.

trend-tracker Genevieve Flaven

p.26

Flaven explains that iconic brands create – and occasionally rewrite – their own narratives. …When the jewelery range was launched [in 1993] we were told it was in the spirit of Coco – but in fact she disliked jewelery.

p.29

But if consumers are invited to play a part in the story of a brand, what happens when they subvert it?

…

It’s doubtful, for example, that Dr. Martens encouraged the skinhead movement to adopt its shiny black boots.

…

Burberry faces a similar problem in the United Kingdom. Some time ago, it joined the pantheon of brands adopted by label-conscious but not particulary upmarket British youth, notably soccer fans. As a direct corollary, and most damagingly of all, Burberry – and particualry its iconic check pattern – has become associated with “chavs”. …(“Britain’s peasant underclass” – chavscum.co.uk)

Bruberry – English, quirky and fashionable.

The company has also placed more focus on its check-free upmarket label, Burberry Prorsum, which is a step above the largest range, Burberry London, in both positioning and price.

In short, Burberry has trodden a delicate line between nonchalant acceptance nad ingenious denial of the phenomenon.

Lacoste has faced the same challenge in its native France, where the prestigious sportwear with crocodile logo has been adopted as a uniform by tough teenagers from the banlieues, or suburbs.

p.31

But when French hip-hop fans began casting around for a home-grown version of the sports brands worn by their American counterparts, they naturally turned to Lacoste. The logo implied performance, taste, and money to burn. Plus, what could be more rebellious than that snappy little croc?

A myth is fragile and easily tarnished.

functional four-by-four – паркетник

p.64

Velosa elucidates: “It’s known as “confetti buying” or “confetti press”. Whether you are a buyer at barney’s or the editor of a fashion magazine, it’s the same principle. You have to dedicate 80 per cent of your floor space to your mega-brands, or 80 per cent of your editorial to your biggest advertisers. So you left with 20 per cent of what’s called “coneftti” – the fun, new and innovative stuff that you sprinkle around to make your store or your magazine look fresh and interesting.”

p.64

Velose explains that New York was chosen because Paris and Milan collections are dominated “by huge advertising brands and heritage brands”. With heavyweigh controlling everything, it’s almost impossible to get a good slot in schedule – and if you don’t, you’re immediately regarded as b-list.

p.66

Williamson: “I don’t think fashion is theater, so my clothes aren’t costume or avant-garde.” …I’m particulary thinking of Missoni, Chloe, Pucci and Marni. Those four labels are international fashion brands, but they’re not necessarily hosehold names.

p.71

At the beginning of the 19th century, French shopkeepers were still mired in a positively medieval system. Historically, access to trades and professions had been regulated by a system of unions. Traders were required to specialise in a single product or service and could not, legally, branch out into other markets. Firms were passed from father to son, and business was done with regular customers on a one-to-one basis, often by appointment. Clients rarely ventured beyond their local vendors. Prices were not displayed, and bargaining was expected. This meant there was little need for advertising, window displays, or any other form of visual merchandising.

The system was scrapped in 1790, but fo more than 30 years traders stuck tenaciously to the traditional structure. It was only in the 1820s that a new type of boutique, called “magasin des nouveautes”, began to appear. Grouping textiles, parasoles and other items under one roof, these small shops developed revolutionary techniques like tempting window displays, clearly marked prices and the division of merchandise into aisles.

p.76

‘There was a time when all the chain stores were using posters and bust forms in their windows. I imagine it was because they’d spent so much money on their advertising that they wanted to squeeze maximum value out of it, so they put posters in the window, too. It was a classic case of what happens when the marketing departament drives display side. Now it seems to be swinging back the other way – you’re seeing mannequins again and more creative displays.’

p.77

But the most powerful expression of architecture-as-branding comes from Prada, whose Epicentre stores perfectly express its intellectual image. The locations are designed by the hippiest architects: Herzog & de meuron (best known in the UK for the Tate Modern art gallery) in Tokyo; Rem Koolhaas in New York and then Los Angeles.

p.79

Running in tandem with the Dover Street venture, she has also introduced the concept of Guerilla Stores. These hit-and-run outlets will open for only 12 months at a time, taking over semi-derelict building in the edgiest districts of cities. …The strategy acknowledges that, being naturally suspicious of anything ‘corporate’, the new generation of consumers prefer to mine information from underground seams.

p.82

Technology naturally affects trends, too: the resurgence of tweed was provoked by manufacturing developments that made the fabric lighter, more supple and easier to manipulate.

…

At the other end of the chain, if retailers tacitly agree to support certain color or fabric trends, it means heightened customer demand, guaranteed sales, and less remaindered stock – which they might have been saddled with if they’d veered off message. Hence, fuchsia one summer, lavender the next; this season linen and denim, next season velvet and corduroy.

Trend Counceling

Nelly Rodi, Promostyl, Peclers and Carlin International.

But WGSN is no fly-by-night dotcom – it sees the web merely as a means to an end. “We’ve never used the term dotcom internally”, Trerde says, “because it has all the wrong connotations for us. We perceive ourselves as a research and information company that just happens to use internet as the quickest means of diffusion.

Other trend-trackers act not as much as consultants to the fashion industry, but as observers of cultural shifts that may have an impact on product development. Onse such agency is Style-Vision, founded in 2001.

Ironically, though, the only people really in touch with the latest trends are those who create them – on the streets. Consumers themselves, particularly young ones, are more ocinoclastic, inquisitive and inventive than any designer armed with WGSN password and a stack of trend reports. No sooner has marketing executive told adolescents that this is the correct way to wear a pair of jeans, than they’ve torn them off the waistband and started wearing them differently. The classic argument runs that, once a trend crossed over into the mainstream, it is already out of date.

Brands who try to target niche opinion-formers without doing their homework often find themselves exposed to ridicule. …If you’re using somebody who’s not a respected artist, the result may not be obvious to you, but it’s extremely obvious to people within the scene, which undermines your credibility as a brand.

Hence her recent brush with Mexican gang members…

“I’ve occasionally wondered about that myself, but I think attitudes to age are changing. I’ve got lots of friends who are older than me and who are still very much involved in the scene. There’s a graffiti artist called Futura 200 who’s 50 years old and still considered an icon of cool.

The image-makers

p.93

While other brands hire international advertising agencies such as J. Wlater Thompson, Saatchi & Saatchi or BBDO, fashion brands tend to work directly with a narrow pool of freelance talents.

According to art director Thomas Lenthal, who has worked for brands such as Dior and Yves Saint Laurent, “In fashion, there are probably only about a dozen well-known art directors, great photographers, stylists, make-up people, and so on. You don’t need an advertising agency: you just need an address book with a handful of names in it.”

Portrait of an art director

p.96

Lethal recalls. “We were doing something very different at the time. The French magazine market has improved immeasurably since the 1990s, but back then publishers were determined to deliver exactly what they thought the female population was expecting. We didn’t want to produce a woman’s magazine, but a fashion magazine. We discovered that 30 per cent of our readership was male – not just gay, but straight too. They liked girls we used, and there was solid arts and culture coverage.”

p.97

Although ads can look similar, codes saturate the image, and the target audience receives the message almost subliminally.

The combination of Galliano, Lenthal and Knight resulted in one of the best-known examples of the style that became known as “porno chic”. “Guilty as charged”, says Lenthal. “We did a controversial campaign featuring two gorgeous models [Gisele Bunchen and Rhea Durham] embracing each other and seating. It was almost a new start for Dior, because it was bold, extreme and arrogant.”

Later came the collection Galliano called “Trailer Park chic”. The related advertising imagery, says Lenthal, consisted essentially of “tarts covered with grease on a scrap heap”. He cackles delightedly at the recollection: “Once again, it wasn’t exactly something you’d associate with a French fashion house. The consumers loved it.”

p.98

Lenthal feels that the brand is ‘particularly rich’ – starting with the YSL logo, designed by the poster artist Cassandre in 1963, which remains unchanged. He says, ‘With Saint Laurent you have so much to explore, particularly the way he makes colors clash instead of trying to get them to blend together. He is famous for his daring color palette. He also designed for a certain type of woman, so when you’re doing the casting you naturally look at the kind of models he used in the 1970s.

p.107

Corinne Day became notorious for creating the so-called “heroin chic” look, with a series of photographs featuring Kate Moss. The pictures, which appeared in the June 1993 issue of British Vogue, showed the model looking wan and undernourished, clad in vest and knickers and posing in a dingy flat. The shoot, which spawned hundreds of pale facsimiles, contributed to the “grunge” fashion trend.

p.108

In terms of trends, he(Vincent Peters) believes that fashion photography has become less narrative and more conceptual:clients are looking for the big idea.

…When people outside of fashion say that all advertising looks the same, they aren’t paying attention to the details. but at the luxury end of the market, where I tend to work, consumers notice details.

…He adds that, in any case, great art has often been commercial: “Look at Renaissance painters, or look at Mozart: their best work was commissioned by wealthy patrons.”

…Most models have a precise image that either works of the brand or it doesn’t. Some of them are more couture, others are sexy…

p.112

In early Vogue editions, dresses were worn by wealthy socialites – although they were gradually replaced by ‘normal’ girls. For many years, models were little more that clothes-horses…

The London of the 1960s changed all that. …By letting the heat of their (David Bailey and Jean Shrimpton) sexual relationship into their pictures, by letting their models seem touchable… they transformed themsleves into fashion’s first real celebrities outside fashion.

p.112

Lesley Hornby, a sweet girl from Neasden, was initially represented not by a modeling agency, but by her mentor and boyfriend Justin de Villeneuve. Her colt-like frame, all arms and legs, earned her the nickname Twig’, which evolved into ‘Twiggy’. When she let a hairdresser use her as a model for a new style – a short, elfin cut that emphasized her enormous blue eyes – her future was assured. She climbed quickly from the pages of the Daily express to Elle and Vogue.

p.117

“We don’t wake up for less than $10,000 a day”, Linda Evangelista famously told Vogue in 1991. The quote was the defining phrase of the supermodel era.

…although agency (Models 1) boss John Horner agrees that the supermodel craze have faded. ‘Versace really put supermodels on the map. He decided he’d pay whatever it took to get the best models, which started the inflation process.

p.118

Horner dislikes the term ‘clothes-horse’, but admits that models play the role of a blank canvas. ‘They are there to interpret and enhance a product. The more flexible their face or body, the more easily they can create a distinctive image for the client.’

Celebrity sells

p.122

The benefits are as blinding as a spotlight: stars give brands a well-defined personality for a minimum of effort, and bring with them a rich fantasy world to which consumers aspire. In addition, consumers have a ‘history’ with stars. Even though they’ve only seen them on the screen or in the pages of magazines, they form an attachment to celebrities, regarding them as friendly faces and reliable arbiters of taste. Models, with their distant gazes and alien bodies, can’t compete.

p.124

‘Sex and the City’ has finished its turn, but it helped to convince image-makers that the buying public related more to the perceived ‘realness’ – however illusory – of actresses than to the unattainable beauty of models. Stars began to replace models on the cover of fashion magazines (as of 2003). “The fashion press is very much gagged”, he says. “This is not just about advertising cash – it’s also about gifts and holidays. The connection between fashion brands and the media is based on relationships, and fashion PR people work very hard to stimulate friendships with journalists. It’s very difficult to write nasty things about your friends.”

p.130

The methods fashion editors use to choose the clothes they feature merit a brief explanation. Most of them rely on “look books” – a sort of catalogue sent to them by the fashion brands to present each season’s collection.

p.132

There’s no doubt that glossy magazines wield tremendous marketing clout. Over the years, the fashion press has handed many designers a place in history. It was Carmel Snow, the editor of American Vogue, who wrote of Christian Dior’s designs in 1947: “This is a new look!” And the support of Helene Lazareff, the founder of Elle, was fundamental to Gabrielle Chanel’s comeback in 1954, when the designer was severely out of favor – having ill-advisedly spent the Occupation shacked up in the Ritz with a German officer.

p.132

As the likes of LVMH and Gucci have acquired more brands, they’ve been keen to market them. Their system is to buy a fashion or luxury business, improve the product, and then tell lots of people about it very quickly.

p.133

So what can magazines do? Coleridge smiles mischievously: “they may smooth-tongued publishers to instil a sense of fairness and balance into proceedings.”

p.134

Didier Grumbach is president of the Federation Francaise de la Couture, du Pret-a-Porter des Couturiers et des Createurs de Mode. in other words, he runs the organization that runs the Paris collections.

…

As far as the Paris collections are concerned, the federation’s power is absolute. For one thing, it decides which journalists will be admitted. Editors must submit forms providing the circulation figures of their magazines and specifying the names of the reporters and photographers who will be covering the event. Their requests can be rejected. The final list is sent to the fashion designers and their PR representatives, who then choose which journalists they wish to invite.

p.139

Grumbach also stresses the importance of what he call “the godfather figure”. Prospective members must secure the support of an established name in fashion who can state their case before the election committee. “It’s necessary to have a sponsor who can speak on your behalf, and explain why you should be admitted. This is, never forget, a club. If Christian Lacroix sends a letter insisting that you are the next big thing, it helps. And if Jean-Paul Gautier is advising your company – bearing in mind that you are, in some ways, his competitor – we generally respect that.”

He adds that the sponsor should be the president or CEO of a fashion brand, not just a designer. Once again, although fashion is a creative industry, executives have the greatest influence.

p.141

These days, most buyers place orders at private “pre-collection” gatherings in showrooms, during which the designers present straightforward commercial versions of the garments they will alter send out on to the catwalks. … Some of the brands sell as much as 70 per cent of their wholesale stock at pre-collection. So by the time the catwalk collection comes around, if the pre-collection was received positively, the designer feels much more confident and free to experiment. Shows are therefore becoming less commercial and more theatrical. They are less and less a direct selling tool.”

p.141

Didier Grumbach himself admits that there are perhaps only 1,000 haute couture customers in the entire world. I have heard estimates as low as 300. In Paris today the official list of permanent haute couture designers stands at 11: Adeline Andre, Anne Valerie Hash, Chanel, Christian Dior, Christian Lacroix, Dominique Sirop, Emanuel Ungaro, Franck Sorbier, Givenchy, Jean Paul Gaultier, and Maurizio Galante.

p.145

The third reason [for haute couture existence] – and the most humane – i simply to preserve the craftsmanship that goes into haute couture. As well as the people who work in the designer’s atelier, there are a number of cottage industries adding the luxurious touches that give these outfits their appeal. The embroidery house Lesage, the glove-maker Millau, the milliner Maison Michel, exquisite feather creations from Andre Lemarie and lace from Puy-en-Velay – all these traditions might be lost if haute couture were to vanish for ever.

p.146

Lesage

“Naturally, [the designer labels] are keen on accessories because they provide greater profit margins,” she(French fashion journalist Janie Samet) says. “And customers like them because no matter what else you are wearing, if you have the right bag, you are immediately placed in a certain context. The problem is that if you have the right bag, the right shoes and the right belt, you may decide that you no longer need the right dress. In this way, the success of bags is killing fashion.

p.152

The age of international travel was dawning, with railway lines extending their steel fingers across France, and the first steamers traversing the Atlantic. Their wealthy passengers required a great deal of luggage – the more elegant the better. Spying a growing market, Louis Vuitton decided to start his own business.

p.153

the secret of Louis Vuitton’s continuing success was the fusion of luxury goods with fashion: ‘Monsieur Arnault invented what might be called “luxe-mode”. He devised a way of persuading customers that a luxury item was a fashion statement, and therefore needed to be renewed or replaced.

p.155

There are only a handful of fragrance houses in the world, and every scent on the market has been designed by one of them. The most famous are IFF (International Flavorus & Fragrances), Firmenich, Givaudan, Haarman&Reimer, Takasago, Quest International and Sensient Technologies. As well as gfragrances, they conjure up aromas for food companies.

p.159

Three-quarters of the world’s perfume bottles are produced by some 60 enterprises and 7,000 workers in the Vallee de la Bresle, not far from Dieppe in northern France. The largest, Saverglass, produces a million bottles a day.

p.160

Kim Winser observed that in the 1950s and 60s Pringle had been ‘an amazing, glamorous brand’, and noted that advertising images form the period featured curvaceous ‘sweater girls’ in Pringle jumpers. In a stroke of genious, the sexy Sophie Stahl was recruited as a modern-day sweater girl for an advertising campaign.

p.168

And when you look at the men’s magazine industry, it’s about 17 years old. This generation of men is the first that has been acclimatized to spending money on fashion. It started with the rise of style magazines in the 80s, when men started seeing images of themselves projected back at them for the first time. … And this is combined with the rise of menswear in Britain – which was basically kick-started by Paul Smith – made it very exciting period for men’s fashion.”

p.172

His[Hedi Slimane’s] friend and adviser Jean-Jacques Picart says, “There is an almost military discipline about Hedi’s suits. They are designed in such a way that it’s impossible to slump when you’re wearing them. You have to hold yourself straight or they don’t look right.”

Picart adds, ‘Hedi brought a sort of sensuality to the metallic and the graphic. There’s nothing curved or soft about his designs. It’s a dramatic contrast to the absolute glamour that Galliano is providing for women. A Dior woman could never live with a Dior man. Bernard Arnault [who hire both designers] created equilibrium via opposites. He delivered the extreme for both sexes.’

p.173

Le style anglais was undermined in the 1920s by the Americans, who began experimenting with a new style of relaxed fashion.

American influences dominated the 1940s and 50s, as well. The young zazous of Paris, with teir over-long jackets and greased-back hair, looked like cartoon versions of Chicago gangsters. Fashion historian Francois baudot observes that the scene was closely linked to jazz, swing and the jittebug – possibly the first example of youth trend that combined music and dress.

p.175

zoot suiters—the men, the women

At core, zoot suiters were rebellious outcasts, young minority groups who believed themselves victims of social suppression and unfairly-treated social rejects. They resented the culture that had cast them out and were determined to defiantly flaunt what made them different. Their odd manners and dress were symbols of defiance calculated to prove the worth of their own values and way of life. Their peculiar manner of speech—their jive talk—echoed in the zoot suit song, was a flag that signaled their differences; it was meant to distance those who didn’t belong, as was their flamboyant style of dress.

Zoot suits were popularized and promoted chiefly by Mexican Americans, African Americans, Puerto Ricans, Italian Americans, and Filipino Americans during the late 1930s and 1940s. The style is thought to have originated in El Paso, Texas during the 1930s. Hence, many chicanos or Mexican Americans refer to El Paso as El Chuco.

The Zoot suits, with their yard-long key chains, high-wastes, wide lapels, wide legs, tight cuffs, and glistening shoes, were not merely articles of clothing or a style of dress; they were a symbol of an outré lifestyle and of all the divisive issues that simmered beneath the surface of daily life. Many of the men who wore them believed that they had been isolated from society through no fault of their own; they felt caught in a world they believed was not as cool as their own.

The Mexican American male zoot suiters called themselves pachucos (in salvadoran culture chuco means dirty). They spoke their own dialect of Mexican Spanish, called Caló or Pachuco. Mexican American woman who dated zoot suiters or who had similar feelings about their lives sported their own version of a man’s zoot suit and called themselves pachucas. These women often wore a V-neck sweater or a long, broad-shouldered coat, a knee-length pleated skirt, fishnet stockings or bobby socks, platform heels or saddle shoes, dark lipstick, and a bouffant hairdo. Sometimes they donned the same style of zoot suit that their male counterparts wore. With their striking attire, pachucos and pachucas constituted a new generation of Mexican American youth.

Etymologists believe that he word zoot is a rhyming compound based on the word suit. It was part of their Caló slang that stemmed from the Mexican Spanish pronunciation of the English word suit with the s sounded as z.

the zoot suit

An anonymous entertainer jitterbugging alone on stage wearing a zoot suit costume. Notice the extended forefingers.

The zoot suit and A Zoot Suit were statements of these views, and more. In effect, the zoot suit was a party costume worn on the streets or at weddings, galas, and dances—anywhere flamboyant dress-up was acceptable. And The Big Bands were part of this celebration, the source of the Swing they danced to.

Why have a good time when the nation was at war? Many Zoot suiters had a nasty little secret that gave them something to crow about: they were accidentally or deliberately overlooked by draft boards because of their immigration status. Many others were classified 4-F, the draft board designation for physically, psychologically, or morally unfit for service.

True, many zoot suiters did not escape the war’s impact. In time the draft caught up with some, while others eventually volunteered. Some served with distinction, fought, were wounded, or died. And most had hard-working families at home to worry about or brothers and sisters in the military.

But the bulk of zoot suiters had good cause to believe themselves immune from the kinds of bad news that was filling newspaper pages. They could care less about who just won or lost a major battle in far away Europe or Asia or whether the tide of war might soon be turning in favor of the U.S.. They were largely oblivious to such matters.

Moreover, they had good reason to believe that living conditions for them would remain the same after the war. They were bored and had little else to do but party; so what did they have to lose by having a ball?

For reasons like these, as a social class Zoot suiters were cool at a time when cool was out (not in) for the rest of the nation. They were young, second-class jive cats who were out of work at a time when factories were buzzing full-time and out of uniform when twenty million men were fully committed to war.

But others in America did have something to lose. For America, the age of the flapper was dead and gone forever; the U.S. was now reeling from the double blows of depression and world war. Garish fabrics and bright colors were out; blacks and grays and olive drab were in. This was no time for a block party as far as the rest of the country was concerned; this was a time to wear black.

The full-length jackets and sleeves, the copious folds in extra-long baggy pants and cuffs, were making the wrong statement at the wrong time. It was bad enough that cloth was rationed. Far worse, mothers were sewing blue and gold stars on small blue and white pennants hanging in frontroom windows, each star a sign of a son or other family member killed or wounded in the Service. To the rest of the nation, zoot suits were a symbol for outrage.

the zoot suit riots

Both sides resented each other and clash among the factions was inevitable. It wasn’t long before the zoot suit style of dress, which had started in the late 30s among Mexican Americans, African Americans, and Italian Americans as a symbol of social unrest, evolved into a street gang fashion.

The zoot suit was not worn by everyone; one estimate puts the figure at twenty-to-thirty thousand. But that was enough to foment trouble. In 1943, for ten days a series of so-called Zoot Suit Riots broke out in Los Angeles between white servicemen, civilians, and police on one side and Chicano zoot suiters, on the other, culminating in arrests and trials, some on trumped up charges.

At their height, the riots involved several thousand men and women fighting with fists, rocks, sticks, and sometimes knives. This succession of altercations, which came to be known as the Zoot Suit Riots, led to property and bodily damage and many arrests, but no deaths. Outrage and police crackdowns rapidly brought to a close this period in American history.

A zoot suit (For My Sunday Gal) was an integral part of the Big Band era, when it was cool to be cool in America, but only in certain circles. The vast majority of “circles” varied from conservative to ultra conservative. Most of America was square. There were many more “not cool” people than cool people. The differences between them gradually caused friction, which heated up until it boiled over into the streets of wartime Los Angeles. A succession of riots lead to some deaths and many arrests, rapidly bringing to a close this brief, tragic, but colorful period in American history.

The mentality behind A zoot Suit (For My Sunday Gal) was an integral part of the zoot suit scene. What mentality did the song and the suit give voice to?

Zoot suiters were not alone; they were not the first subculture to express their feelings of rebellion and individuality through their dress, and they will not be the last. One outstanding example comes from the Zazous of WWII France, a group of rebellious Parisian youth who balked at the the restrictions imposed on their free-living life style by the Nazi occupation and the Vichy regime.

Surprisingly, the word Zazou probably was inspired by Cab Calloway, the famous American Black Jazz artist. Here’s the story of how this happened:

Parisian youth were jazz and swing music fans long before war came to France; Jazz was alive there when the Germans took over the city. From their parents they knew about the Black jazz scene that had sprung up in Montmartre during the inter-war years when Black American entertainers, who felt freer in Paris than they did back home, had entertained their parents there.

Cab Calloway had been a prominent entertainer during his protracted sojourn in Paris in the years between the two World Wars. He’d appeared in Montmartre and at many other night spots. The French were familiar with American Zoot Suiters and Zoot Suits through the music Calloway and other American entertainers had played and the Zoot Suits he and some of the others had worn.

The Jazz scene lingered long after the Americans left. French musicians like Stephane Grappelli, who’d learned Jazz from Black entertainers during the ’20s, were actively recording and playing their brands of Jazz in cabarets; Gypsy musicians like Django Reinhardt, who soloed and teamed with Grappelli, helped keep Le Jazz Hot alive by recording and playing swinging jazz music in Parisian boîtes.

Then, early in 1942, a popular French crooner named Johnny Hess released a song called Je suis swing in which he sung the lines Za zou, za zou, za zou, za zou ze.

Hess’s lines were strongly reminiscent of a line in a song often sung by Calloway called Zah Zuh Zaz. The song spoke to them of the wild times and the good old days when Paris once was free.

That’s all the Parisian youth needed; it set them on fire. They coined the word zazou, which recalled the title of Calloway’s song, and named themselves after it. (Notice the phonetic resemblance between zah zuh and zazou.) They patterned their style of walk and dance after American Zoot Suiters and their style of dress after the Zoot Suit. Cab and his Zah, Zuh, Zaz had coalesced and set in motion the Zazou movement.

The Zazous of WWII had created a subculture in France that was inspired by zoot suiters in America during World War II, but their cause was different. During the German occupation of France, the fascist Vichy regime, which had collaborated with the Nazis, had forced an ultra-conservative morality down their throats. It had enacted a battery of laws aimed against what ultraconservative Frenchmen saw as a restless and disenchanted youth. The Zazous expressed their resistance to this oppressive regime through their nonconformity.

For the most part, Zazous were simply young Parisians asserting their individuality. They did this through a variety of means. They held aggressive and combative dance competitions, sometimes brazenly inviting German soldiers and making them victims of their aggression. They wore excessively big or garish clothing modeled after American zoot suit fashionry at a time when clothing was rationed. And, like zoot suiters, they danced wildly to swing jazz and bebop.

The amount of material used to make a suit, which was as excessive as possible given fashion and clothes rationing, made a comment on Government decrees rationing clothing materials. Men wore extra large lumber jackets, which hung down to their knees and which were outfitted with many pockets and several half-belts. Their trousers were narrow but gathered at the waist. Their ties, which were made of cotton or heavy wool, also were gathered. Their shirt collars were high and kept in place by a horizontal pin. They favored thick-soled suede shoes and white or brightly-colored socks, and their hairstyles were greased and long. They frequently wore sunglasses, perhaps to symbolize that they were looking the other way where the Nazi occupation was concerned.

Zazou women also wore garish clothing—short skirts, striped stockings and heavy shoes; and they and often carried umbrellas, perhaps to symbolize the metaphorical rain that was falling on their lives. They wore their hair in curls that fell to their shoulders or was braided—blonde was a favorite color—and they wore bright red lipstick. Ladies wore sunglasses and sported jackets with extremely wide shoulders like their male counterparts; or they wore short, pleated skirts. Their stockings were striped or sometimes netted, and they wore shoes with thick wooden soles.

The growing influence of Milanese designers was apparent in the dance-floor sheen of disco, but the Brits, doing rather better out of the deal, had saved themselves by embracing punk rock.

p.176

He (Carlo Brandelli) adds that the ‘correct’ colour palette for the English male is charcoal grey, navy, white and sky-blue. Anything else smacks of the trendy.

p.179

‘…The other problem for the photographer is that masculinity is a more psychological concept that femininity. I would argue that it’s easier to capture femininity visually’. This explains the frequent use of established male role models as brand reference points.

p.181

The early 20th century saw the launch of two sport-shoe brands: Reebok, produced in England by Joseph Foster from 1900, and Converse, founded by Marquis M. Converse in Massachusetts in 1908.

p.185

Adidas can trace its roots back to 1926, when the brothers Adolf and Rudi Dassler established their sports-shoes business in Herzogenaurach, Germany…. The pair’s wartime experiences are said to have caused the split that pushed them to go their separate ways. Adolf (Adi) created the Adidas brand (from the first syllables of his given name and family names) while Rudi founded Puma. The two brands became fierce rivals.

p.186

The 1970s was a decade when jogging came to the fore as a leisure activity, helping to nudge sportswear further into the mainstream. It was a market in which Puma’s products proved especially popular, enabling it to gain ground on Adidas for the first time. But trouble had materialized for both brands in the form of a brash young upstart called Nike.

p.187

The Swoosh would begin its rise to omnipresence when Andre Agassi won the men’s tennis chamionship at Wimbeldon in 1992.

…

Knight and Bowerman… began making their own trainers in 1972. Their first shoe, the Nike – named after the Greek goddess of victory.

p.187

Reebok proved particularly adept at spotting and capturing the emerging aerobics market, which even Nike had failed to anticipate due to its male-oriented, sports-star culture.

p.188

A few months after the purchase, Converse released an advertising campain narrated by the rapper Mos Def. The shoes were seen on famous feet, and fashion editors began to write about how they’d been wearing Converse for years. In the background, those in the know could hear the roar of a marketing machine getting into the high gear. Before long, the shoes were everywhere again.

p.190

According to Tom Vanderbilt, ‘Athletic shoes are to other shoes as sports utility vehicle are to other cars: large, loaded with impressive but rarely-used options, a statement less of need than of desire.’

p.191

Two trends that were prominent in the late 1980s and early 1990s – sports shoes without laces and oversized jeans worn so low that the wearer’s underwear waistband is visible – have something in common. They were both started by criminals.

p.192

By the end of the decade, the association of sports shoes with street culture was getting out of hand, with media reports of urban teenagers being slain for their expensive branded shoes. Along with claims that, in Asia, children were being paid peanuts to make sportswear, the stories contributed to a brief downturn in the sector’s fortunes.

p.193

At that point (1998), says Massenet (Pert-a-porter), ‘the online community was largely male. Now fashion is one of the largest categories in online retail, and there are more women than men online.’

p.197

One criticism of fashion on the web is that it robs designer brands of one of their key selling points – the brand experience. When you’re not buying your expensive shirt in a sleek retail hub attended by gorgeous staff, is it worth the same amount?

p.198

‘The internet is the only medium that can keep pace, while the glossies still have three- to four-month lead times. Over time, their only choice will be to evolve into big, beatiful coffee-table books.’ (by Natalie Massenet)

p.200

Esprit, which started life as an American brand, is now headquartered in Hong Kong.

p.216

Dickson Poon agrees that mrketing to Chinese consumers is tricky: ‘Irrespective of how liberal China may be with its financial reforms, I believe it will maintain strong control over the press and the media for a long time to come. This means… one will not be able to buy into the market through effective and appropriate advertising. Therefore, even if the market may not yet be totally ready, the opening of shops may still be the best way to introduce and to educate the Chinese consumers about the image, lifestyle and products of a luxury brand.’

p.216

One of Nike’s greatest rivals in CHina is Li-Ning, which sells US$200 million worth of sports shoes a year. It takes its name from its founder, Li Ning, a former gymnast and winner of several Olympic gold medals. Its scything logo is as dynamic as the Nike Swoosh, and its slogan is ‘Anything is possible’.

p.218

Mid-market chain stores are feeling downward pressure on their prices, thanks to the increased availability of cheap merchandise in the form of cut-price casualwear sold in supermarkets.

p.219

As the traditional home of luxury goods, France has long been a victim of the counterfeit trade. Associations such as the Union des Fabricants, established way back in 1877, and the more recent Comite Colbert, founded in 1954 (its glittering list of members runs from Baccarat through to Yves Saint Laurent), have battled to raise international awareness of the problem.

p.222

This rise in expertise has led to the ‘super fake’, an item almost identical in quality to the real thing. He went on to say that investigators frequently went missing.

p.223

There have been frequent raids on New York’s Canal Street, which resembles a black-market bazaar… Such scenes normally take place just a few blocks away from Barney’s or Bergdorf Goodman. Elsewere purse parties have replaced Tupperware parties as a leisure pursuit, with women buying counterfeit bags from dealers and selling them in suburban homes at a profit.

p.224

It’s much harder to fake a Bottega Veneta bag, whose authenticity is announced via its supple woven leather than any visible logo. (Indeed, the brand’s marketing mantra )

...

Martin Margiela’s labels are simply numbers, although each signifies a specific line. Udo Edling’s jackets are identifiable to aficionados via a series of visual codes: one pocket (on the right), darts above the shoulder blades, and the reverse of the collar in Alcantara microfibre rather than in felt (a different color each season).

...

Already, most Western fashion and sportswear companies are not apparel manufacturers, but apparel marketers. Behind the familiar brand names are lesse-known supply-chain management companies such as Li & Fung (Hong Kong) and Makalot Industrial Co. Ltd (Taiwan), which co-ordinate the production of graments and footwear for their more famous clients.

p.231

In the 1950s, European teenagers wanted to get their hands on original American jeans. Over the years, this evolved into an obsession with retro American which, in Italy, would inspire a young man named Renzo Rosso to start a company called Diesel.

p.241

“For the intelligent consumer it simply means overpriced and over-hyped. The new trend towards thrifty shopping is as much about being ahead of the curve as it is about saving money.”

(‘The drift to thrift’, The Observer, 12 October 2002)

p.242

The quote underlines the theory that ‘vintage’ is an attitude rather than a style of dress. It’s a rejection of ‘exclusive’ yet global brands, an affirmation that cheap an unusual is better that expensive and everywhere – and a message to marketers that the fashion consumer of the future will be harder to snare.

p.245

The appearance of ‘faux vintage’ clothes that paid homage to the past was driven, ironically, by cutting-edge fabric design that brought a new suppleness and practicality to tweed.

p.249

Branding via buildings

In the rich west, shopping is no longer a functional task. It is a form of entertaninment akin to going to a cinema, a show, or even an art gallery. Brands are responding by creting spaces that have more in common with museums or theme parks than traditional stores. These branded environments have become destinations – they are on the list of places to visit when you arrive in an unfamiliar city. If brands insist on a strategy of marketing via architecture, in order to hurdle advertising clutter and distance themselves from cut-price stores, they must provide rich and rewarding experiences.