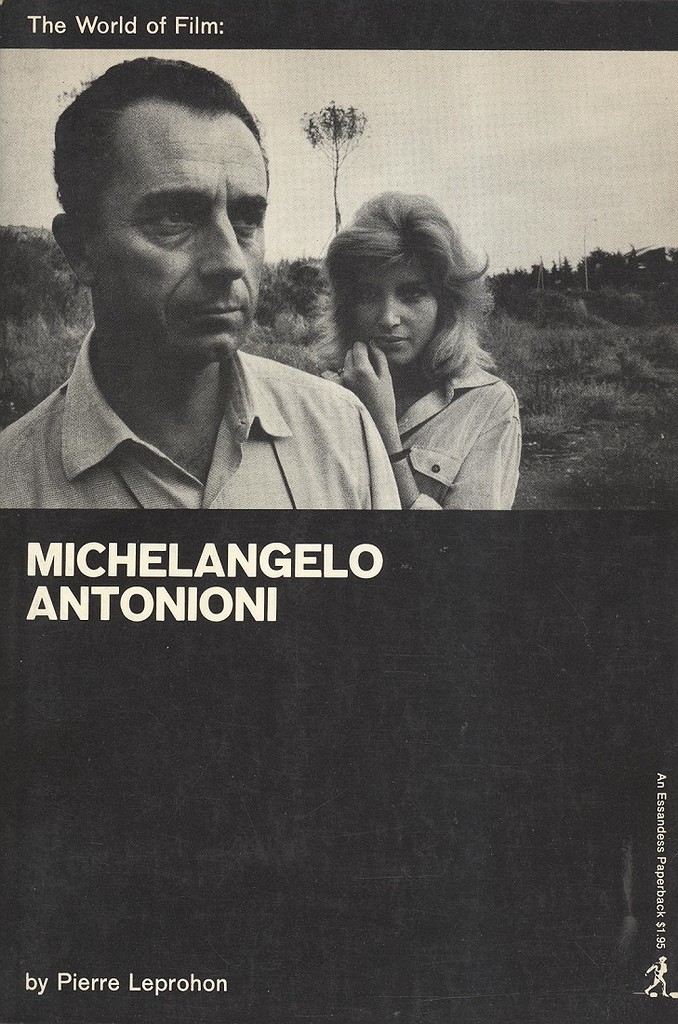

Michelangelo Antonioni - by Seymour Chatman and Paul Duncan

Ted Perry & Rene Prieto - “An Antonioni film is understood not by listening to what the pepople say, although this may ofetn provide nuance and complexity, but by looking at where the people stand, what they > touch, what they look at, and what looks at them… Not only is the landscape used to make general statements about the personalities of the people, but the more specific states of consciousness are expressed

through particular locales. Where an event kates place will tell us more about the event, and its meaning of the people, than what the people say and do… The environment imposes itsef upon the sensibilities

of the characters, influencing their behaviour. Background becomes foreground and foreground becomes background. Each inflects the other.”

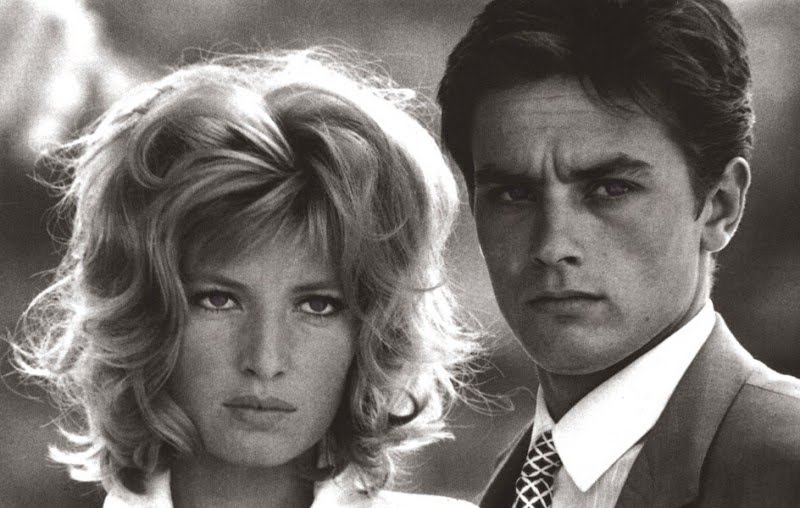

L’avventura (1960)

Pascal Bonitzer - "Lavventura is ostensibly the story of a dissapearance, but a dissapearance whose importance and destiny evaporate little by little, until the very structure and form of the narrative are

perilously contaminated and impaired; what happens in reality is the dissapearance of the dissapearance of Anna (Lea Massari)."

Antonioni described L’avventura as a giallo in rovescia – a’yellow [film noir] in reverse’ – referring to the fact that the victim is never found and that not only is a crime not solved, but that it is unclear whether there was one.

For those who didn’t get the point of Sandro’s frantic womanising and of Claudia’s rediness to frogive him, Antonioni explained that the widespread preoccupation with sex would not be so obsessive “if Eros were unhealthy, that is, if it were kept within human proportions. But Eros is sick; man is uneasy, something is bothering him. And whenever something bothers him, man reacts, but he reacts badly, only on erotic impulse, and he is unhappy.” The source of Sandro’s frustration is made clear enough in the film: he has sold out his own artistic promise for more lucrative commercial consulting work. He has failed to strike the ballance between love and meaningful work that Freud found essential to well-being, and he uses the former to compensate for his failure to achieve the latter.

What is adventure? Antonioni said:”The characters in the film live an emotional adventure – it involves the death and the birth of a love – a psychological and moral adventure which makes them act in contradiction to the established conventions and the criteria of a now outmoded world.” The film clearly doesn’t celebrate philandering, but it also doesn’t condemn it on traditional moralistic grounds. Sandro’s erotic and professional confusion – he suffers from what Antonioni called a malattia dei sentimeni (an emotional sickness) – are to be pitied, not praised ot condemned.

Antonioni argued the split between the achievements of science and the “rigid and stereotyped morality” prevalent in modern society. The consequence is that human beings are “burdened with a heavy baggage of emotional traits which cannot exactly be called old and outmoded but rather usuited and inadequate. They condition us without offering us any help, they create problems without suggesting any possible solutions”.

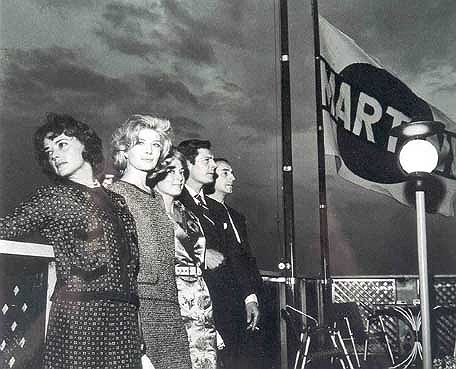

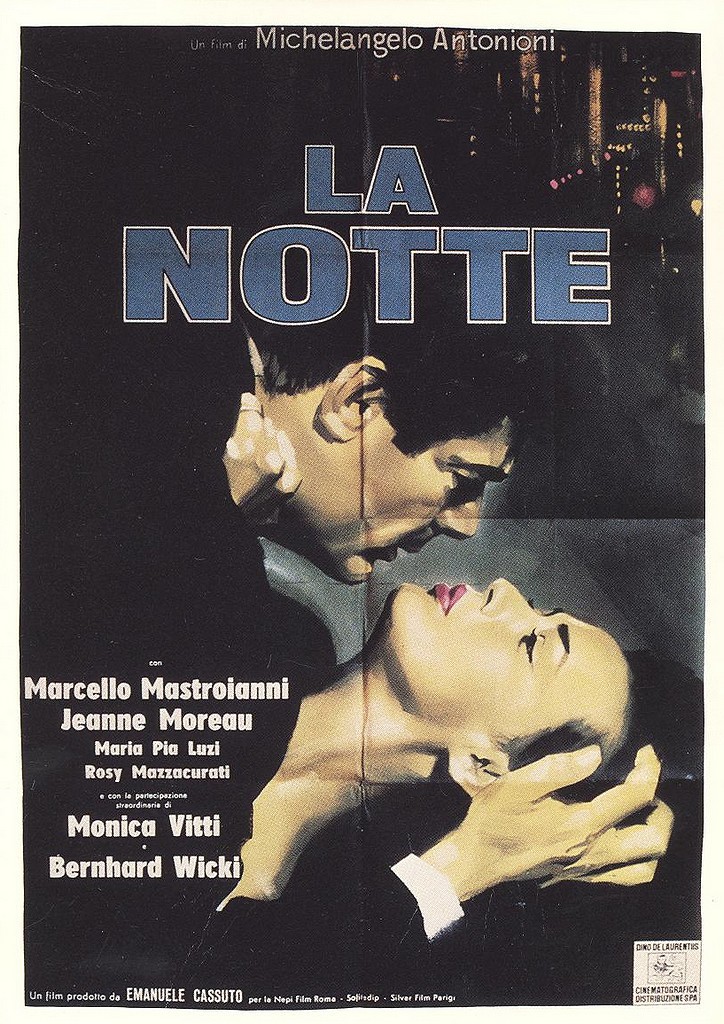

La notte (1961)

Like Claudia in L’avventura and Vittoria in L’eclisse, Lidia is the most stable character in the film. Antonioni explained that women appealed to him as characters because he found them more in tune with their feelings, and therefore more honest. …the female protagonists seem to do best because they trust their instincts and get on with their lives. Lidia may or may not be making a mistake in giving in to Giovanni’s gropings in the golf bunker, but whatever the outcome, we feel that she will emerge with a clearer mind than he.

In fact, Antonioni preferred to use dialogue to conceal character’s thoughts and feelings: they tend to say precisely not what’s on their mind or relevant to their immediate situation. So the audience is constantly asked to guess what they are thinking.

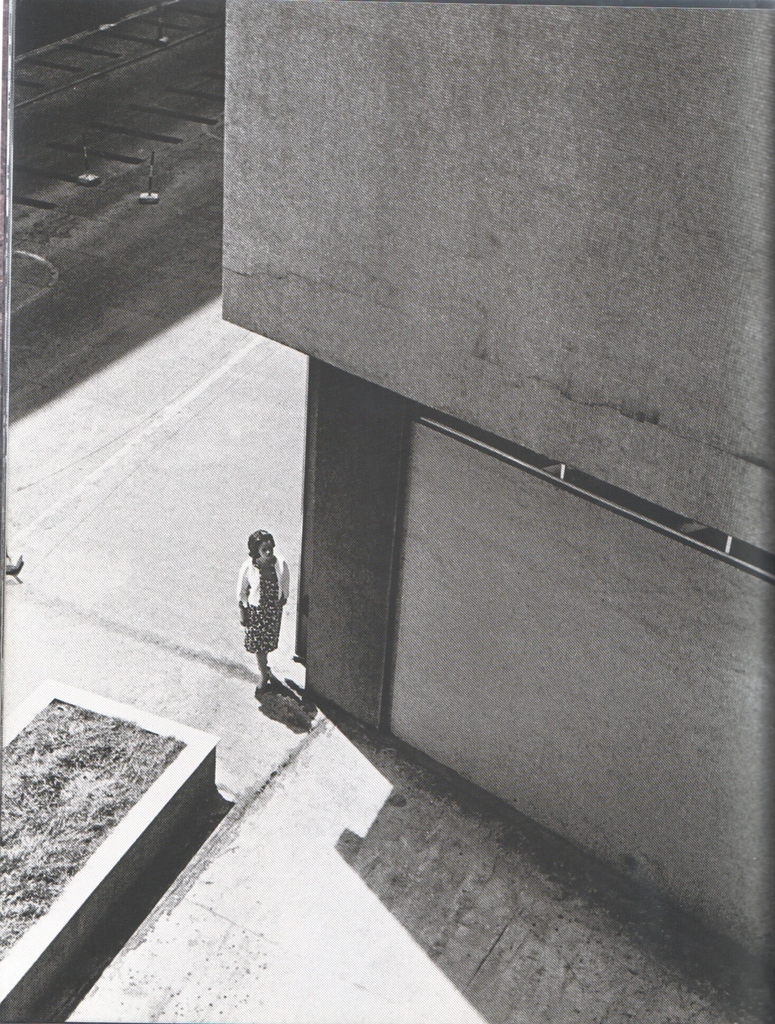

He (Antonioni) was showing, audaciously in the absense of verbal explanation, the impact of architectual gigantism on the individual and how the old values of community were dissapearing simply because people no longer had a place to be.

Rudolf Arnheim - "…the fenestrated wall of a high-rise building… may be experienced as empty even though the architect has put something there for us to look at. The effect of emptiness comes about when the

surrounding shapes do not impose a structural organisation upon the surface in question. The observer’s glance finds itself in the same place wherever it tries to anchor, one place being like next; it feels

the lack of spatial coordinates, of a framework for determining distances. In consequence, the viewer experiences a sense of forlorness."

Le’Eclisse

No actual eclipse appears in the film, so the title takes on a symbolic quality. It conveys the sense of how normal emotional life is disturbed – “how feelings stop” – in the ominous advent of the atomic age. The film’s heroine, Vittoria (Monica Vitti), is a sensitive but upbeat and self-sufficient young woman.

Two unrelated events show Vittoria’s capacity to enjoy life on her own: one is a visit to the neighbouring flat of Marta, an Englishwoman just back from Kenya, whose African artefacts fascinate Vittoria; the other is a flight in a small plane to Verona.

По материалам:

Taschen

anna-lee

Philippe Lubac